I had Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night before me during silent reading time at the beginning of my math class. Shakespeare had always been a struggle for me, but now all of a sudden things starting clicking. I was catching the flow of the narrative, keeping up with the witty banter, excited to see what would happen next to the characters.

When there was a long, steady trumpet note somewhere in the classroom, I didn’t let it phase me. I kept reading. I was in the zone. When the trumpet’s note ended, I realized with horror that the sound had emanated from me. I had been so into the text I didn’t even notice myself release a toot.

All my peers started laughing, asking, “Who was that?” I said nothing, trying to look as amused and bewildered as everyone else. I was one of a handful of students taking math at the other high school, so people didn’t know me that well. It seemed like I was in the clear (which was good, because I had a crush on the girl sitting behind me!).

The next day, I was sitting at my desk before class started. One of my friends from middle school (who now went to the other high school) was talking to someone else in the back of the classroom. He said, “You should talk to Nate. He’s the one who farted yesterday.” So, it turned out my wind solo was not anonymous after all.

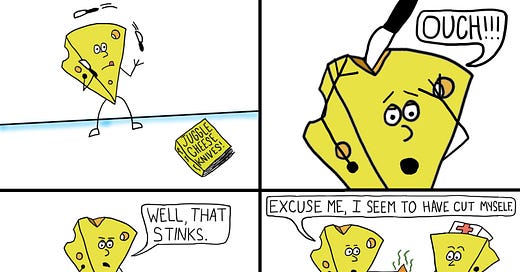

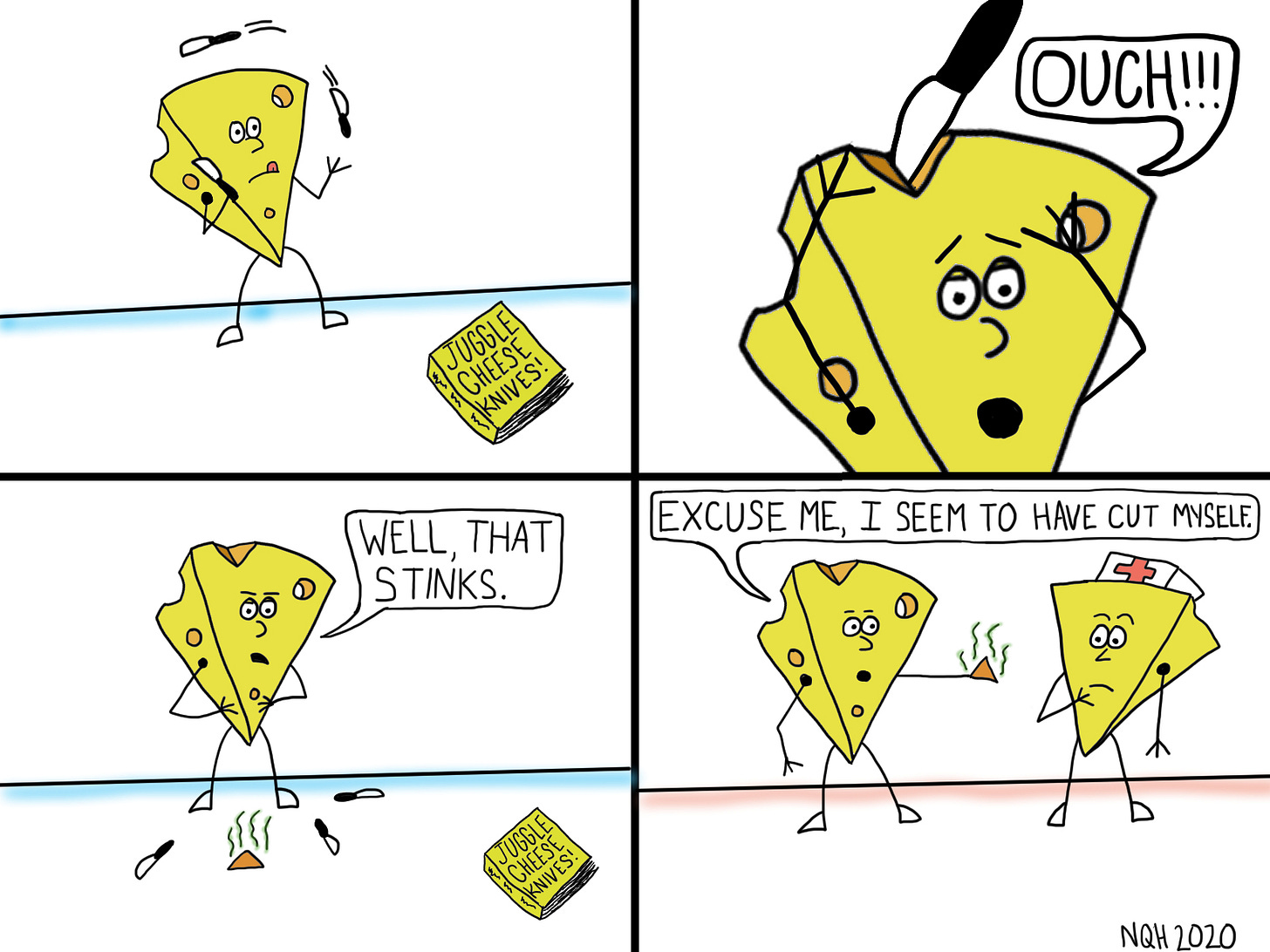

I am not an expert on flatulence. I would, however, consider myself an expert on flatulence-related humor, a genre I have engaged in since I was old enough to find farts funny. I like to believe that my gas-passing jokes have become more refined with age (what you might call “noble gas”), as the following cartoon demonstrates. (But in the end, it’s still just a fart joke.)

Recently, I’ve been wondering about the literary value of flatulence. It’s of course not a challenge to put a fart in a story or poem, especially if you want to add in some humor. When I was growing up, I encountered many farts in books made for boyish guffaws. But could flatulence have a place in serious literature?

In other words, could a fart contribute something to the meaning of the piece? Could a fart be more than just a stinky, comical presence? What could be learned from existing literary farts, and how might those inform my own writing? I haven’t done a lot of research, but here are my reflections on two farts I have encountered in my reading recently.

1: Fart as Spiritual Metaphor

John Donne, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, chapter 6

This is a book of devotions and theological meditations, which Donne wrote in response to a life-threatening illness (from which he eventually recovered). In each chapter, Donne writes about a different “stage” of having an illness—from the first inklings that something is amiss to doctor visits to treatments to recovery. He reflects on mortality, sin, repentance, salvation, various virtues and vices, theology, and spiritual practice.

Chapter 6 is an exploration of the difference between fear of God and other kinds of fear. At the beginning of the chapter, Donne writes:

As the ill affections of the spleen complicate and mingle themselves with every infirmity of the body, so doth fear insinuate itself in every action or passion of the mind; and as wind in the body will counterfeit any disease, and seem the stone, and seem the gout, so fear will counterfeit any disease of the mind. It shall seem love, a love of having; and it is but a fear, a jealous and suspicious fear of losing. It shall seem valor in despising and undervaluing danger; and it is but fear in an overvaluing of opinion and estimation, and a fear of losing that.

In this passage, bad gas (“wind in the body”) is used as an analogy for fear. Gas moving through the intestines may feel so uncomfortable that we wonder if something else is wrong with us, something far worse than the need to fart. We think of “the stone, the gout” without necessarily recognizing the “wind” behind our feeling. Gas can wear different masks (a “gas mask,” you might say).

In the same way, fear can wear different masks. We may think we act from love or valor, but we are actually acting from a place of fear. Fear of losing is behind our “love of having.” Fear of losing the respect of others is behind our so-called valor. We want to be perceived as fearless, and in so doing, fear losing that image.

It is a brief reference, but Donne’s meditation on bad gas leads to a deeper spiritual insight. Perhaps we, too, could consider the ways that flatulence might be used metaphorically.

2: Fart as True Self

Stephen Dunn, “Often the Pleasures of Departure”

This poem is from Dunn’s 2003 collection, Local Visitations. It begins like this:

Often the pleasures of departure are so close

to the genuine sadness of leaving

he feared his goodbyes

would reveal it, an errant tone perhaps

at odds with a sincere word.

And though he knew that anyone’s heart

might lean two ways at once,

he also knew that no one could be comfortable

with such a truth, not even himself.

The protagonist of this poem recognizes that we can feel both sad and happy when departing. Maybe, thinks the “he” of this poem, my happiness at leaving is stronger than my sadness—I’m worried that will show when I say goodbye.

The second half of the poem seems to function as a defense, a justification of the protagonist’s feelings. These are the pertinent lines for our exploration of flatulence:

It wasn’t necessarily that he’d be going

to someone else; it simply could be

the relief of farting a great private fart,

or that aloneness itself was his mistress.

The poem suggests that while infidelity could be one reason the protagonist is happy to leave, other explanations are arguably more valid, more meaningful. We’ll hold on the fart for now. Perhaps “aloneness itself was his mistress.” For the protagonist, solitude is something to be desired, and he can meet his solitude only clandestinely. He worries his goodbye will betray how pleased he is to leave. Likewise, he hides the joy he finds in solitude, worried it will hurt his partner.

“It simply could be / the relief of farting a great private fart.” Take a moment to admire the consonance of this line: the relieF oF Farting a great priVate Fart. The repeating f/v sounds resemble the noise a fart might make on its way out of the body—or at least the onomatopoeia that might be used in a comic strip panel.

Now let’s look at each major word in turn:

the relief: How many of you know the relief of letting rip what you’d been holding in for hours at a friend’s house? Of course, there’s the physical relief of pressure easing in the bowels. But there’s also the relief that, once you’re alone, you don’t have to worry what others will think about your fart (the sound or the smell). You can listen to your body instead of social etiquette.

of farting: In this line, Dunn uses the word “fart” twice, once as a gerund verb and once as a noun. The repetition signals the significance of the fart. This isn’t just a passing image in a list of “what you might do while alone.” Dunn is asking us to reflect on what the fart might mean, how this “crude action” might shed light on the philosophical question at hand: should we feel guilty when we feel pleasure at leaving those we love?

a great: Well, we can’t avoid it: this is a great fart. “Great” of course, could mean big, mighty, terrifying. “Great” could also mean good, satisfying, necessary. The wonderful thing about poetry is that it can evoke multiple senses of a word at once. We don’t have to find “the” meaning, but can explore the possibilities of different evocations. A “great” fart—I’m sure you can imagine it. Maybe you even have a particular memory of one, whose “greatness” cannot be forgotten.

private fart: Once again, we return to the idea of solitude. There’s something wonderful about a private fart. When you’re around others, especially strangers or friends, farting can be embarrassing. Even if you’re with family or a committed partner, if you fart, you’ll probably get a comment about the sound or the smell (or likely both). But by yourself, no matter how stinky your toots, you don’t have to feel the shame of what others might say or think. You can let loose, be yourself. You can let your guard down when you’re alone, relaxing your pelvic floor so the gas can release naturally.

The “relief of farting a great private fart” can certainly be taken literally: the physical and psychological relief one feels when farting in solitude. But there’s also a metaphor here. A fart is like our true self. When we are alone, we can be ourselves. We don’t have to hold in what might be socially unacceptable. There is a part of ourselves we hide from the world, even from our closest friends, family members, partners. Perhaps this is because we feel that to reveal it would be shameful, akin to releasing a foul stench in the room.

It is healthy for us to have our own moments and places of solitude, so that we can understand ourselves for who we truly are, smell what smells emanate from deep within.

In this poem, Dunn has included a fart that resonates both physically and spiritually. Sometimes, you just need to fart on your own terms. And sometimes the fart can be a metaphor for how we need solitude to truly understand ourselves, smells and all.

What wonderful joy to study literary flatulence! I hope you enjoyed reading this. More importantly, I hope you can imagine how other mundane or crude or disgusting things in life might be useful as metaphors and images, how they might point to deeper insight. This is one of the pleasures of literature: creating significance and value in things that might otherwise be overlooked or disparaged. With meditation and imagination, any ordinary experience can yield spiritual insight. The next time you fart, consider what new metaphor or insight it might reveal to you.

And now, to get it out of my system (and yours!), a list of fart puns I couldn’t deprive you of:

For this post, I wrote a lot of fluff.

I hope you don’t think this post stinks.

This post is a work of fart.

At times, this post may have been a bit cheeky.

I hope this didn’t fall flat-ulent.

I’m not just full of hot air!

Not trying to toot my own horn here.

I hope you catch my drift…

This post may linger a bit...

Hopefully this post makes scents to you.

You’ll have to read this post in odor to understand it.

Consider this a toot-orial on literary flatulence.

Thanks for reading! Whiff gratitude,

Nathaniel Q Hoover