One of my lifelong delights is finding strange little quirks in our language, noticing what is often unnoticed. I keep lists of these odd phenomena, and someday I’m gonna do something with all those lists.

Here are some examples:

Add a Letter (or many letters)

Sometimes it is possible to add a letter to a real word and make another real word. I divide these into three groups: prefix, infix, suffix. The most popular prefixed letter (so far in my ongoing creation of these lists) is the letter “s”:

word = sword

exist = sexist

edition = sedition

elect = select (that seems fortuitous)

laughter = slaughter (a chilling pun used by the Joker in The Dark Knight)

Hades = shades (also fitting)

naked = snaked (suitable pun for Genesis 2–3?)

“R” is so far the most abundant infix:

potion = portion

hose = horse

ionic = ironic

potable = portable

But “i” creates some of my favorite infixes:

realty = reality

salvation = salivation

plates = pilates (and plate = Pilate)

gentle = Gentile

defied = deified

party = parity

patent = patient

homoousia = homoiousia (a key debate in early Christianity; look it up!)

By far the most prolific suffixed letter is “e”:

brows = browse

butt = butte

dens = dense

divers = diverse (interestingly, divers used to be an acceptable spelling of diverse)

dud = dude

German = germane

urban = urbane

human = humane

secret = secrete

sing = singe (you know, if a song is “fire”)

stamped = stampede

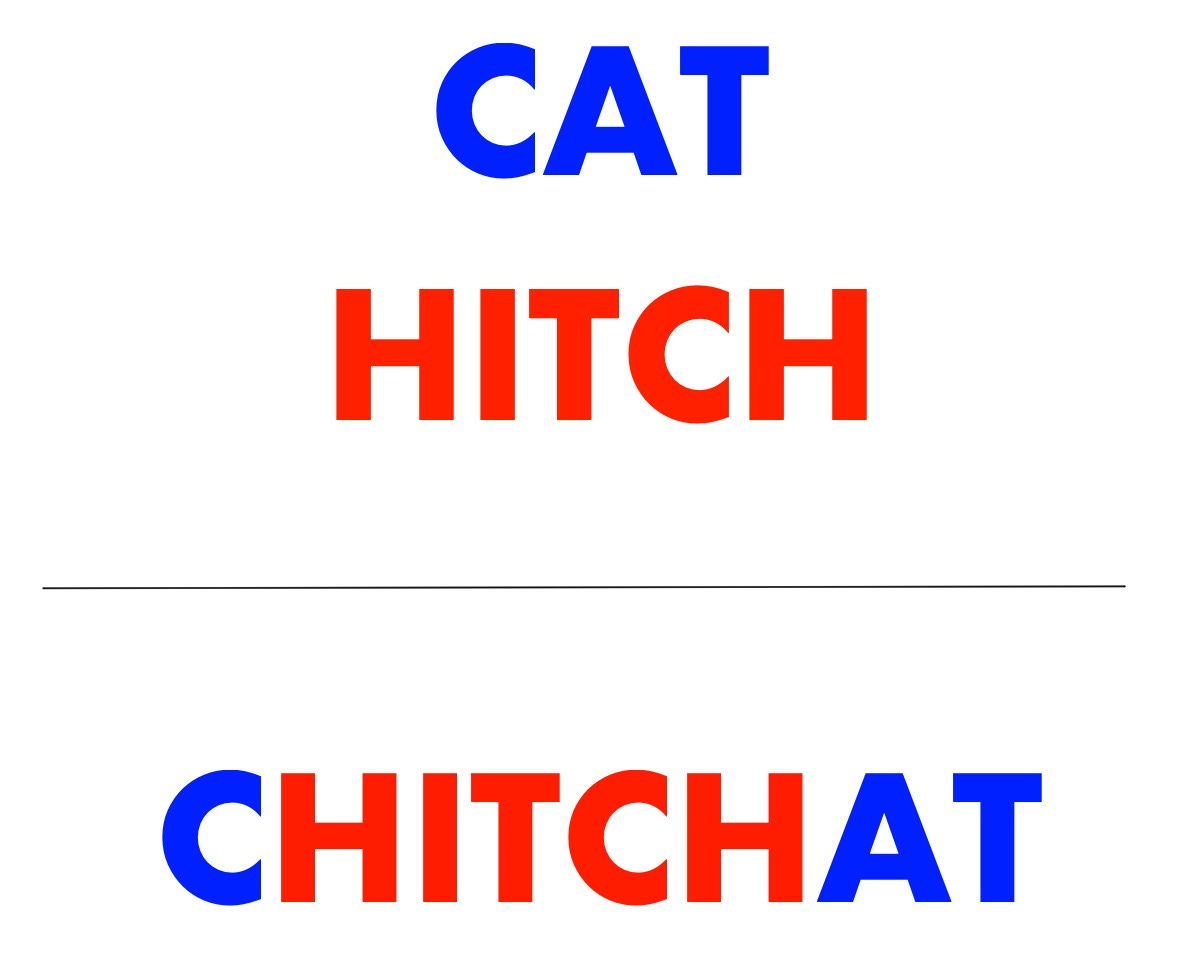

And of course, I also keep a list of real words transformed into real words by the addition of multiple letters at a time. My favorite of these: one word swallows another word whole to make a new word. (The all caps word swallows the lower case word in the examples below):

CAT hitch = ChitchAT

ALTER time = ALtimeTER

CAKE lamb = ClambAKE

SHIES moot = SmootHIES

DEER sign = DEsignER (got that from a student when I said I’d give extra credit to anyone who could find one of these words)

WEAR bin = WEbinAR (another one from a student)

SPRING latte = SPlatteRING

SLING ouch = SLouchING

SERENITY dip = SERENdipITY

FORTE tuna = FORtunaTE

COAL loss = COlossAL

And not quite “word + word = word,” I can’t get enough of just finding words within other words:

You can’t spell homeowner without “meow.”

You can’t spell moreover without “Oreo.”

You can’t spell psychopath without “chop.”

You can’t spell Pharisee without “arise.”

Pluralizations

There are a host of words which, when expressed in the plural, refer to something completely different than their singular counterpart.

For example, being a handyman is fine, honorable even. Being a handsy man is not. Below are some of the more obvious examples of this phenomenon (clothing names and financial terms seem to be commonly in the plural):

tight - tights

overall - overalls

khaki - khakis

short - shorts

slack - slacks

fatigue - fatigues

panting - pantsing

belonging - belongings

possession - possessions

good - goods

future - futures

holding - holdings

double-team - doubles team

billing - Billings

new - news

in and out - ins and outs

bang - bangs

blue - blues

fixing - fixings

Pilate - pilates

Voiced v. Unvoiced

Sometimes the same word (with the same basic meaning) is pronounced differently depending on context. Read these out loud and see what you notice.

I used to be used.

I have to have it.

Did you notice that in the first sentence, the initial “used” is unvoiced, pronounced as “yoost,” while the second “used” is voiced, pronounced as “yoozed”?

And in the second sentence, it goes “haff to havv”? It’s the same word in the same sentence, but voiced differently.

This may seem like a harmless quirk, an odd tidbit that doesn’t have (or haff?) much bearing on everyday life. But let me tell you a story.

This winter and spring, my wife and I were in a small group at our church. Each meeting, our facilitator had us read an opening prayer as a group. One of the lines—read by the “leader”—goes like this:

This is the day that the Lord has made

and a day we’ll have to make our way through.

Read those lines out loud to yourself. How did you voice the “have”? Did you say “haff” or “havv”? The difference in vocalization makes a difference in meaning.

When I initially read it in my head, I pronounced it “haff.” “This is the day that the Lord has made, and a day I suppose we’ll just haff to get through, you know.” Some days feel like that. Yes, we can say “This is the day that the Lord has made,” but in reality, it can feel like we’re dragging through it, like it’s full of drudgery, dread, depression, and/or doom. Does this reading—“haff”—give a pessimistic view of the day ahead? Perhaps it does. It may also put the burden of “making our way through” on each person, as if God has given us this day and it’s our job to not let God down.

On the other hand, “haff” might recognize the struggle involved in “making it through” the day. “Haff” reminds us that time moves in one direction, that—as the prayer goes on to say—“whether with ease or pain, with patience or joy” we will have to endure to the end of the day. “Haff” may not be a comfort, but I do think it can resonate with those who may feel more of the burden of life day-to-day.

But when one of the group members, who was the prayer “leader” that day, read the line aloud, they said “havv.” It struck me as odd. That was the wrong pronunciation, I thought. But then I saw the possibilities of “havv.” “Havv” is much more optimistic. “This is the day that the Lord has made, and another day we get to have available to us to journey through.”

“Havv” sees the day (seize the day?) as an opportunity to live, an invitation to the fullness of life, with its ease and pain, patience and joy. Whereas “haff” perceives the day as an obligation, “havv” perceives the day as a gift. To “haff,” the day is a burden bearing down on the shoulders. To “havv,” the day is a treasure in hand.

Two weeks in a row, I anticipated “haff,” and I was surprised both times by the reader who said “havv.” Why did I think the word could only be pronounced “haff”? What does that reveal about my mindset, or about my emotional state in those moments? I was delighted to hear “havv,” to havv my expectation upended. To perceive both possibilities is a gift, like being able to see both images in the duck-bunny illusion. It’s not about which reading is “correct.” It’s about what effects each reading creates. And about why someone might say one pronunciation over another.

A quirk in language—a revelation.

Reading Scripture

Speaking of pronunciation, I have sometimes had the privilege of reading the day’s scripture passage to the congregation. One time, I was assigned Genesis 3, which, as you might know, involves a talking snake, some nudists, hide-and-seek, God cursing up a storm, and a lightsaber.

Okay, okay, so really, a talking snake convinces Adam and Eve to eat forbidden fruit, and instead of becoming wise, they just realize they are naked. When God shows up (I like to imagine God is whistling a lively tune), the two humans hide. God says, “Where are you?” and this is where I faced a dilemma. How to read God asking this question?

In some church traditions, you might get the angry voice, loud and quick: WHERE ARE YOU!!!? This is the God quick to punish, quick to assign guilt. The easily-angered parent, the disappointed father. What God later says to the snake (“cursed are you”) and the humans (“more pain and toil and death”) is a punishment.

Another option is concern, quiet and breathy: Where ARE you? When God later lays out the curses (just for the snake and the land) and consequences (for the humans), this is not so much punishment as it is “now here’s what your life will be like”—natural consequences, you might say.

You could also ask the question, somewhat like concern, in bewilderment, emphasizing the first word: WHERE are you?

Or perhaps casual, indifferent: Where are you? As if you were asking the delivery person which door they had arrived in front of.

I ended up choosing the voice of concern that Sunday, but I was sorely tempted to read it in a sing-song voice I might use when playing hide-and-seek with a toddler: Where ARE yooooouuuu? What kind of God does that create in your mind? A God who is game to play hide-and-seek? A bit different than the eager-to-accuse God (who actually sounds more like the Accuser, which in Hebrew is satan).

The way we inflect when we read biblical passages can affect how we interpret them, how they influence our thoughts and actions, our relationships with others. Our ideas about God can be broadened or narrowed by how we read—not just by the words themselves.

An Exercise in Quirkiness

One writing exercise I encouraged—but did not require—my students to try involved writing two completely different scenes (with more than one character) that had the exact same dialogue. You can punctuate differently, combine bits of adjacent dialogue differently, but it has to be verbatim, in order, the same. Here’s a (very short) example from my own attempts at this:

Scene 1:

Felicia stood up to go. “All right, I’m outta here. See you around.”

Todd stood up, too. “That’s it? Where are you going? I could take you, you know.” He pointed to his car parked at the curb.

Felicia smiled. “I’m walking tonight.” She pecked him on the cheek and he blushed. “Call me.” She turned and walked down the sidewalk.

Todd watched her go, then muttered to himself. “Once you can afford it, things will start looking up for you.”

Scene 2:

They were gathered under the bridge. Everyone was tense. Frank opened a suitcase on the hood of his car. Doug looked in, shook his head. “All right, I’m outta here. See you around.” He turned his back on the others and walked toward his car.

Frank pulled out a gun and pointed it at Doug’s back. “That’s it!?” Doug turned around, unfazed by the gun pointed at him, and shrugged his shoulders. He turned again and kept walking away. “Where are you going!?” Frank shouted. “I could take you, you know!”

Doug laughed, as did his crew, their own guns drawn. “I’m walking tonight. Call me once you can afford it.” He and his crew got in their cars and drove off, tires peeling.

One of Frank’s men came up to him. “Things will start looking up for you.” Frank glared at him, spat on the ground, then motioned for everyone to get the in the cars and leave.

Notice how the meaning / weight / presence / timbre of the dialogue changes when the setting changes. In the first scene, the words are tender, vulnerable. In the second scene, they are tense, intense. But the dialogue is the same. The words are the same. It all depends on context, on the context you imagine as you read the words.

Small differences, such as an additional letter or two, a pluralization, a subtle pronunciation change, or a change of inflection, can create large differences in meaning. This is a device you’ll have to use. Or one you used to have. Or one you used to have to use. Or one that you can notice as you read.