My five-year-old is a very picky eater. Beyond the roughly 15 food options he will consume, he refuses to try anything else. If, by luck and pestering, he takes an “adventure bite” of something, it will not be added to his diet, even if he says he likes it. We have allowed him his limited palate, and only occasionally offer him new foods. He’ll grow out of it eventually, right?

One day, he tried a food he disliked six months prior: barbecue-flavored potato chips. Then he tried some plain potato chips. “Do you like those?” we asked. “Yes,” he responded. When he asked for more, I had the urge to say, “No more, they’re unhealthy.” A stray thought stopped me, however. What if potato chips are the gateway for him to try new foods? What if he comes to a wider palate through potato chips?

His path to new foods may look different from what I expect, from what I hope. This got me thinking about life more broadly. Who am I to judge what another person’s path in life is like? Maybe a path that, to me, appears unhealthy is what it takes, in the long run, for that person to become healthy. Maybe a “road to ruin” is the road to redemption. Maybe it takes hitting rock-bottom to find a firm foundation.

At one of the residencies for my MFA program, we were assigned Emily Dickinson’s poems. Bruce Beasley, a poet and Dickinson scholar, was our guest lecturer. He helped us to learn how to read Dickinson poems, which are famously challenging pieces of writing. Part of the challenge is the multivalence of her poems, their ability to yield multiple meanings, connections, and insights. Each word is a world—and each poem is a multitude of words. “You can never overestimate how much is compounded in the words of an Emily Dickinson poem,” Bruce said.

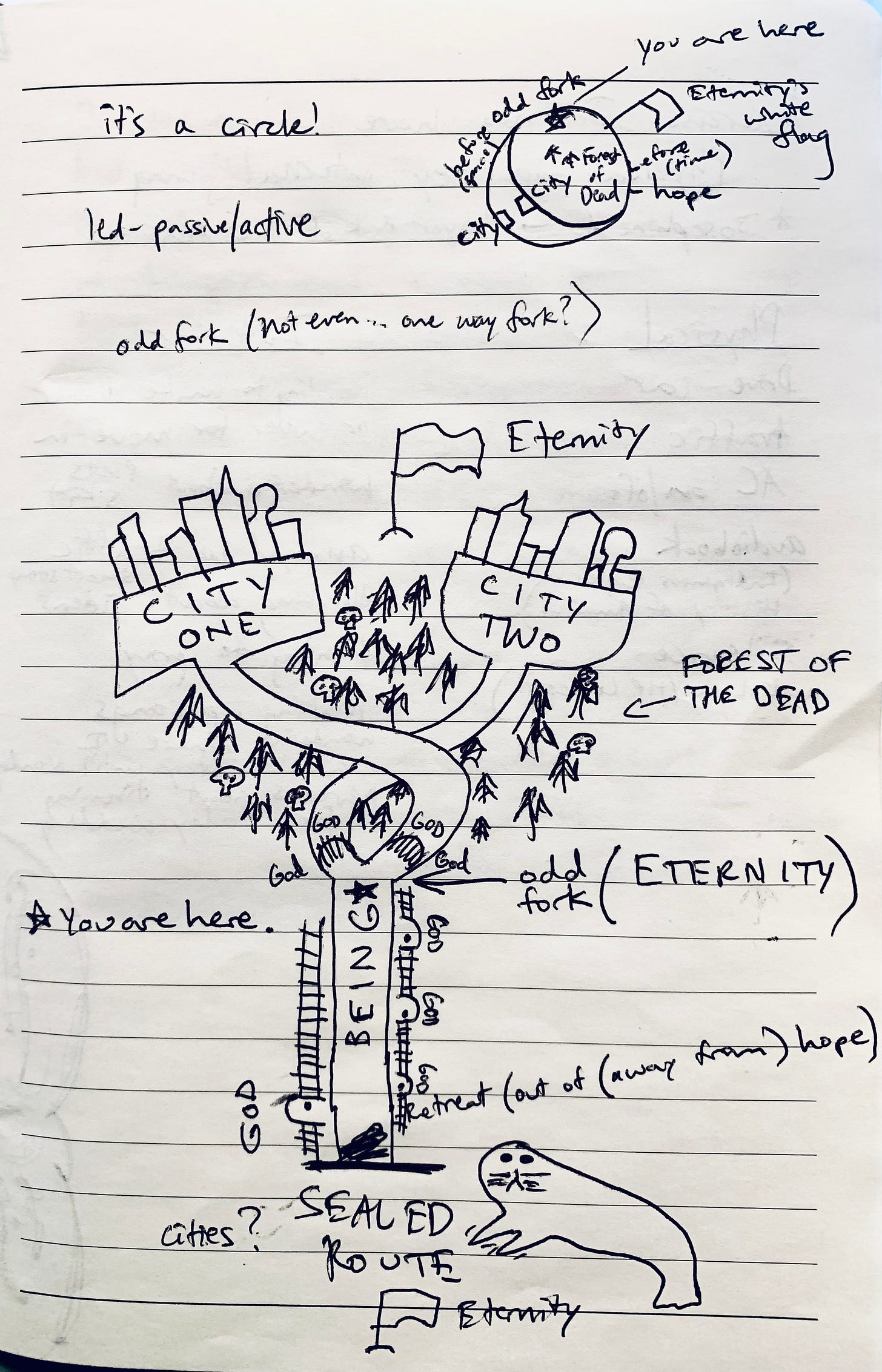

For her poem “Our journey had advanced” (poem 453 in the Franklin edition), Bruce asked us, “Can you map this poem?” We all drew our interpretations of the “journey”: what was before (yet to come, ahead) and what was before (earlier, behind), the “odd Fork,” the Cities, the Forest of the Dead, “And God - at every Gate”. I actually drew two maps (see below), one circular, and one linear. You can read the poem for yourself here.

The poem seems to be about passing from life through death to eternity. But the path Dickinson describes is not straightforward.

First, there is “that odd Fork in Being’s Road - / Eternity - by Term -”. What is the “odd Fork”? “Odd” can mean strange. Eternity seems strange to us who only know life on this side of it. It is unknowable, unclear, mysterious.

Perhaps the Fork is strange because it is always available to us—death and eternity are within our being, able to envelop us in any moment. We don’t pass the fork once, nor can we confidently say it is a long way ahead. The Fork termed “Eternity” moves along with us as we journey. We may have advanced further in time, but the Fork—Death, our on-ramp to Eternity—has advanced, too. It seems always at hand.

“Odd” can also apply to numbers, as in “not even.” By saying “That odd Fork,” could Dickinson imply that it is a one-way Fork? When a road forks, it splits in two or more directions. Perhaps Dickinson suggests that this Fork only “splits” in one. In other words, it is like a bend in the road, because death/eternity is a continuation, a culmination of our life’s trajectory. Yet it is a fork because it takes us to a new path, in a new direction (Eternity). The Fork is “odd” because it strangely has only one direction.

In the second stanza, things get even more perplexing. “Before - were Cities - but Between - / The Forest of the Dead -”. Before is one of my favorite prepositions: it is used both spatially and temporally, and can pretty much mean any direction:

Temporal

Past: earlier (we’ve been there before)

Future: not yet (my whole life is before me)

Spatial

Presence: I went before the king

Ahead: Before us the mountains stood tall

Sequential: I went before the king in the lunch line

So “Before - were Cities” could mean “Cities were ahead of us” or “Earlier, we saw Cities; they are now behind us.” The Cities could be future or past, behind or ahead. How many Cities? At least two.

“Between” is also ambiguous. What is between what? Whether the Cities are ahead or behind, the Forest could be between “us” and the Cities. Or maybe the Cities are themselves between the trees in the Forest of the Dead. Or maybe the Forest of the Dead is between the Cities.

What kind of Cities are these? Are they the Cities of eternity, the heavenly Jerusalem? Or are they earthly Cities, which “were before” and are now obscured by the Forest of the Dead?

The third stanza begins with “Retreat - was out of Hope -”. “Out of” is another multivalent preposition. Does this phrase mean that Retreat had run out of hope—in other words, Retreat was hopeless? This seems to be supported by the second line: “Behind - a Sealed Route -”. Retreat is impossible; there is no hope of retreat back to the past.

But “out of” could also mean “from,” as in: Retreat was sourced from Hope, powered by Hope. Hope is the cause for Retreat. Perhaps Retreat offers some Hope which going forward does not. Or maybe to go forward is to retreat, to retreat into eternity away from earthly life.

The poem ends with these two lines: “Eternity’s White Flag - Before - / And God - at every Gate -”. The white flag likely refers to peace. The peace of eternity is “before.” That could mean it is ahead (i.e., the speaker is still alive, looking forward to the peace of eternity), or what has already passed (i.e., the speaker of the poem is already dead). Regardless, the important thing is “God - at every Gate.” No matter which way the speaker turns, looks, walks, or imagines, God is there at every gate, on every path, in every possibility.

This reminds me of Psalm 139:5–12:

You hem me in behind and before, and you lay your hand upon me.

…

Where can I go from your Spirit? Where can I flee from your presence?

If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.

If I rise on the wings of the dawn, if I settle on the far side of the sea, even there your hand will guide me, your right hand will hold me fast.

If I say, “Surely the darkness will hide me and the light become night around me,” even the darkness will not be dark to you; the night will shine like the day, for darkness is as light to you.

God at every gate. Toward the end of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says, “Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it” (Matthew 7:13–14).

Jesus describes two gates, two roads, one that leads to destruction, another that leads to life. Notice that the road leading to destruction is “easy,” and the road leading to life is “hard.” In our culture, there is an assumption that if one chooses Christian faith, their life will become easier. Jesus promises the opposite. The hard road is the road to life. The easy road is the road to destruction.

Yet, if we follow Dickinson’s lead, and trust in “God at every gate,” then in neither path is God absent. Perhaps for some, the path of destruction is the path to God. This seems to be suggested in the parable of the prodigal son (Luke 14:11–32). Only when the younger son squanders his inheritance and finds himself at rock-bottom does he return to his father’s house, where he is embraced and welcomed. Only after he destroys himself does the younger son find redemption.

Saul persecuted the church before God blinded him on the road to Damascus. Jesus appeared to Saul in a vision while Saul was on a literal road to destruction—destruction of early Christians. On this road Saul was converted, becoming the apostle Paul, an advocate for the church.

Perhaps the “hard road” to life is, in some senses, a road of destruction. Jesus calls believers to die to themselves, to reconsider their loyalties to blood relatives and governments, to sell their possessions and survive off the kindness of others. This goes against what the world considers success. By destroying themselves in the eyes of the world, Christians enter into the hard road that leads to true life (cf. Paul in 1 Corinthians 4:9–13).

God is at every gate: the narrow gate that leads to life, the wide gate that leads to destruction, at the “odd fork,” in the “forest of the dead,” in the cities, on the road, before, behind, in the heights, in the depths, in the light and in the dark, at the far side of the sea. As Paul says elsewhere, “nothing can separate us from the love of God in Christ our Lord,” not “hardship, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword,” nor “death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation” (Rom 8:35–39).

The road that others are on may look like destruction to us. The road that we are on may be a hard one. Let us not judge the road nor the person on it. Instead, perhaps we could say, “They/we are on the road to God.” God is at every gate, whether we take the road that leads to destruction or the road that leads to life. God is at every gate along the easy road and the hard road.

Appendix of Related Quotes

Sin is a great thing as long as it’s recognized. It leads a good many people to God who wouldn’t get there otherwise.

- Flannery O’Connor, A Prayer Journal, 26

Really enjoyed this post. And fun to be reminded of the Bruce Beasley lecture!