Trigger warning: talk of death. At section 16, I tell my own story of child loss.

When my firstborn son died, I learned what it meant to grieve. Grief is not a single emotion, but many, a shifting tide of feelings both physical and spiritual. In the early days of bereavement, I became acquainted with the intensity of my emotions. If my emotions were muscles, they were being stretched beyond what I’d experienced before.

Death of a loved one is a significant event, a life-altering moment which demarcates the boundary between “before” and “after.” It is like a blade severing life in two: who I was when my son was alive, who I am now that he is dead. Bereavement creates discontinuity in one’s life, one’s self-understanding.

Yet there were tiny bridges of continuity, attached right in the middle of the island of grief. The very emotions that seemed to bury me, suffocate me, trap me in darkness were those bridges. Everything I felt in those early days of grief I had felt before. Only now it was more intense. And the emotions I felt were not abstract nouns I could describe—they were tied to specific memories from my past self. It was as if my emotions and my memories worked together to find the continuity required for healing to begin.

What follows are the experiences and awarenesses of death I had before I became a father. Some of these are memories that reached me in the early days of grief. Others have arisen more recently.

1 | Curiosity, Fear

One day in first grade or so, I ride my bike with some other neighborhood kids. We ride to the end of one of the streets and park our bikes at the fence. One kid says, “Look there’s a dead bird!” We all gather around. There are four or five of us, and someone’s younger brother.

On the tar-and-gravel road is a small brownish-gray bird, feathers wet and matted from recent rain. Its yellow beak looks like a flame. I’ve never seen a bird up close. I’ve never seen a dead animal up close. Sure, our cats sometimes leave entrails from shrews or mice, but this is an intact animal, uneaten.

I feel sad. The road feels quiet. It seems like the whole world holds silence for this bird. We stand and crouch around this tiny body, saying nothing. The mystery of death, so enormous, so intimate, weighs on my shoulders, nestles in my stomach.

Then the younger brother grabs a hand-sized rock and brings it down on the bird. His sister yells at him. Another girl cries. When he lifts the rock again, something pink sticks to the surface. To me it seems like bubble gum. Like bubble gum and horror. We get on our bikes and ride quickly after that, as if we are all implicated in a crime.

2 | Fear

I am six. I have been sick for a week. It might be bronchitis. I lie in my bed staring out the window. I can just see the top of the neighbor’s willow tree. I can see blue sky. White clouds glide by. I hold so still I can watch them move. I hold my breath. I am afraid to die. I pray, “Jesus, please don’t let me die.”

3 | Sadness

Every weekend we go to the library. My sister and I check out science videos: National Geographic or Eyewitness News are our favorites.

One week, we check out a movie about life on a farm from the animals’ perspective. There is a scene that follows the activity of a group of kittens. Some of the kittens bully another kitten, chasing it to the edge of a haystack so that it falls to its death. The camera zooms in on the dead kitten’s body before moving on.

Later, on my own, I watch the movie again, rewinding and rewatching that scene, pausing it on the dead kitten’s body. I want to feel the sadness of it. I am fascinated by this feeling—perhaps it is an inkling of my own mortality.

4 | Fear

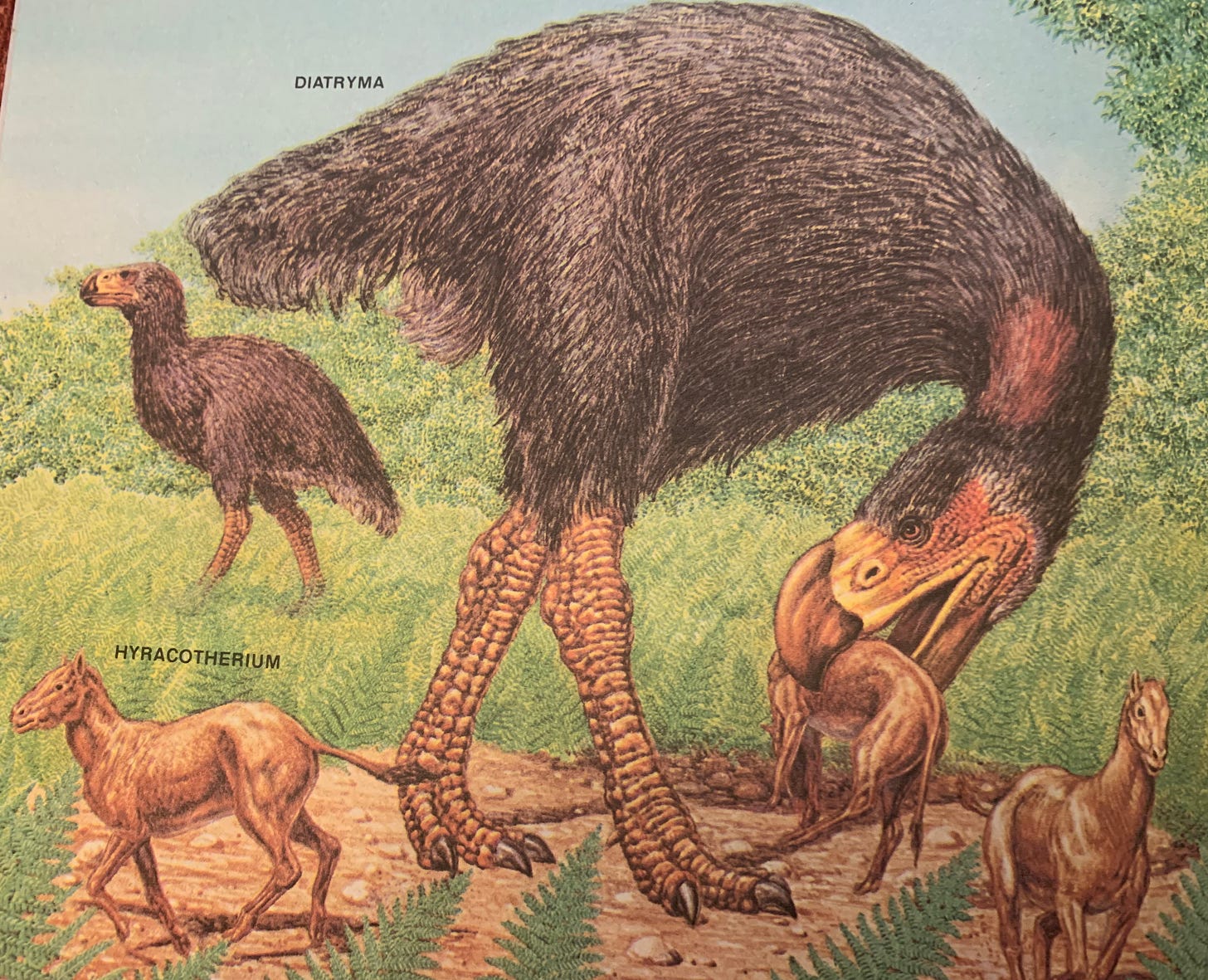

One of my favorite books is called Prehistoric Animals. On one page is a diatryma, a large flightless bird. In the hand-drawn picture, it picks up a small horse in its beak.

Around the same time, I watch the Flintstones live-action movie. In one scene, a pterodactyl poops on a car. It is massive (both the pterodactyl and the poop).

I develop a fear (and fascination) of being eaten by a bird. I know there are no birds in the modern world large enough to eat me. Still, I wrap myself in my “big blankey” and imagine I have been swallowed, that I am being compressed in the stomach. I imagine myself being eaten by a hippopotamus, a pelican, a shark, a crocodile, a python.

5 | Separation, Loneliness

I watch The Land Before Time. I watch An American Tail and Fievel Goes West. There is fear, there is loneliness, there is separation. These are what death means to me.

I watch The Secret of NIMH. When a lab rat gets injected with a substance, it writhes and falls into a black abyss with flashing kaleidoscopic colors. This feels like death to me. Mysterious, terrifying.

I watch The Secret Garden. The scene in which a mighty wind blows and the protagonist’s mom gets sucked away—a dream sequence—terrifies me.

I watch Return to Oz. Nightmare fuel, that movie. I like it, of course. But there is so much dread, so much loneliness, so much to remind me of death, or what I think death is.

6 | Longing

My mom flies on an airplane. My dad, my sister, and I accompany her to the airport, all the way to the gate. The airport is an endless, ominous portal. It is navy blue, the color of dusk, the color of impending sleep and sad, longing-filled dreams. When my mom disappears through the terminal, I wonder if she will be gone forever.

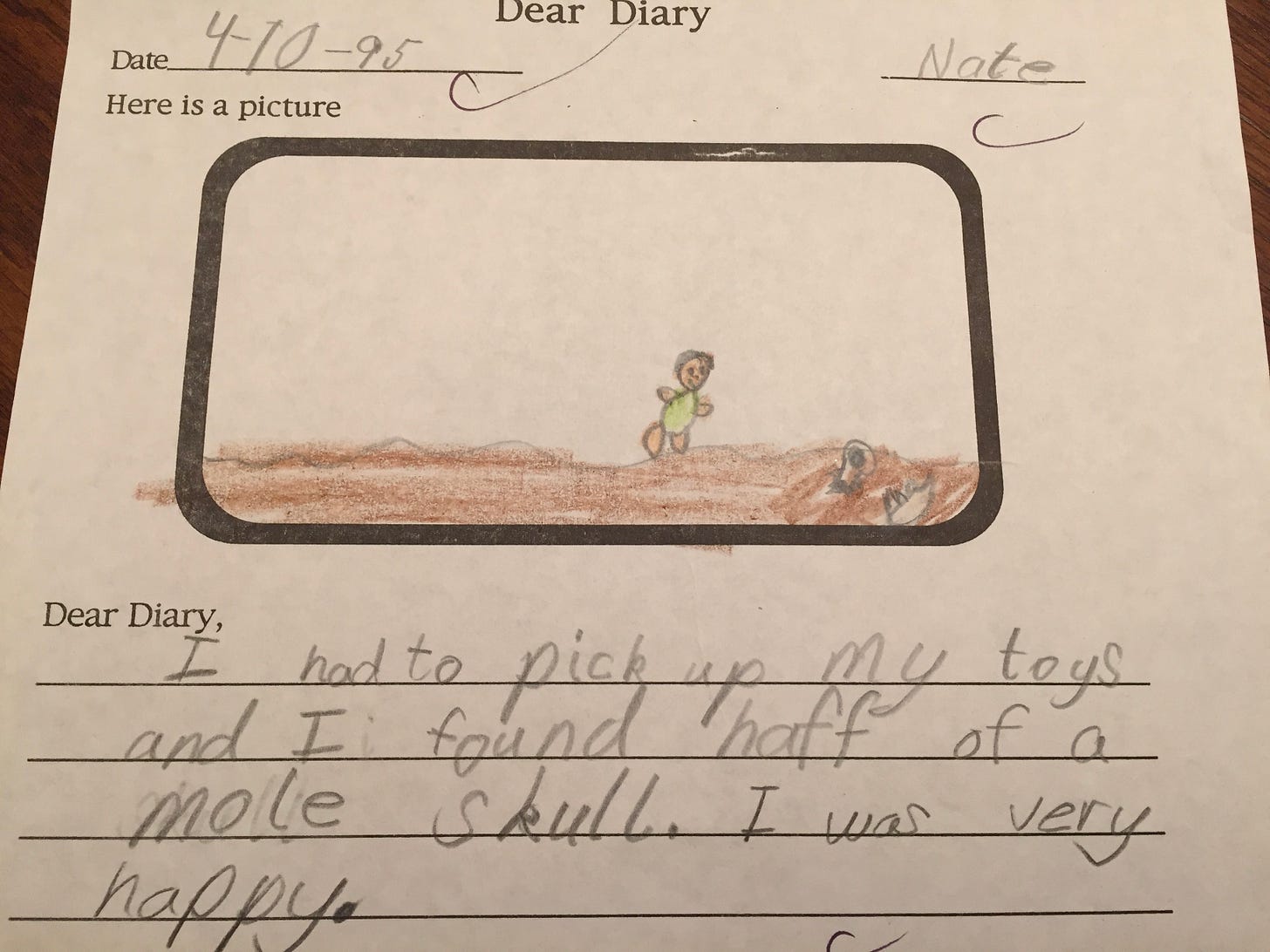

7 | Curiosity

While digging in the backyard dirt, I find a skull of a mole. I write in my first grade in-class journal, “I was very happy.”

8 | Loss

Our black cat, Delilah (“Deli” for short) dies right before we move to a new home. I am only a little sad. She was old; it was better for her to die. My sister and I put her into a shoebox filled with grass. We have a little ceremony. Afterward, my dad takes the box to the dump.

9 | Sympathy

I am in middle school when I attend my first funeral. It is called a “celebration of life.” The bereaved parents, members of our church, are sad, but they both speak confidently at the service. They even express joy that they got as much time as they did with their newborns.

10 | Sadness

In middle school I learn there is someone in my grade who should’ve been there with us, but she died unexpectedly in 5th grade. I feel sadness, pity, but I don’t know the girl, so I don’t think much about it.

11 | Anger, Creativity

I start listening to heavy metal, classic and contemporary (from Metallica to Disturbed). I start writing songs with themes of death, though I don’t really understand what I’m writing. I am expressing my teenage angst, my anger. And I am falling in love with language. I am exploring the process of writing songs and poetry (though I won’t recognize this until much later).

12 | Pity

In the spring of my sophomore year of high school, I have to take the WASL, the state’s standardized test. Our school alters the schedule for two weeks so that we spend the mornings testing with our advisors and the afternoons in our regular classes. Our advisor is one of the Spanish teachers. I have met with her once per year to talk about my academic and career aspirations.

Halfway through the first week of testing, after school, this teacher makes a left turn across four lanes of traffic and another car hits her and kills her. The next day, my group of advisees gets a break from the WASL. There are counselors on hand. I do not feel sadness. I feel pity and a little fear: she had been alive this time yesterday. Death is never far away. Within a week, there is a new “No Left Turns” sign at that particular entrance.

13 | Numbness

I attend my second funeral in my junior year of high school. My paternal grandfather. I sit in the balcony and control the video camera (zoom and pan as needed). At my grandparents’ house after the service, my dad and his four older sisters tell stories I never knew about my grandpa, stories that change my understanding of him.

My paternal grandmother moves back to North Dakota after the funeral. When she dies a couple years later, it feels very distant.

14 | Sadness

I date a girl during my freshman year of college whose sister died in 5th grade. It is the same sister who should have been in my grade. The death impacts me more now. I cry at the telling. Or maybe I cry later, by myself. Aside from the initial storytelling, however, I never bring it up or ask any questions about her grief. Years later, I will regret my avoidance of the subject.

15 | Regret

After my junior year of college, during the summer, my maternal grandmother dies. It is my last grandparent to pass. This grandma moved to my hometown when I was in high school. She was in an assisted living facility for a couple years before moving to a nursing home. Though she lived so close, I rarely visited her in high school (or when I was home from college): another regret.

In college, I met someone from Poland who taught me a few Polish phrases. On my occasional visits to my grandmother, I had spoken these phrases to her. She was delighted. She was the child of two Polish immigrants who met in America. I think it had been a while since anyone spoke Polish with her.

My mom calls to tell me the news. She says, “I wanted to let you know that your grandma is …” She chokes up and the last word is clipped: “dead.” I learn that talking about the death of someone you love can be like reliving it. I learn that telling a new person about the death can bring up strong emotions.

The day of the funeral, which is to take place in Aberdeen, WA, I go to an urgent care facility because of painful sores on my feet. It turns out to be a staph infection. I cry in the car. I am overwhelmed by all that is happening. My own personal illness combines with my family’s grief.

Allison, my girlfriend at the time (now my wife) drives like the dickens from Bellingham to Aberdeen. We expect to miss the interment of my grandma’s ashes. We will make it for lunch. But somehow, by God’s grace and perhaps a little speeding and perhaps a little time dilation, we make it to Aberdeen in just over two hours. My mother’s siblings are at the gravesite. Some of my cousins are there. My sister is there. It is my first time in a cemetery for a burial.

My extended family’s first language is humor. After a few words from a minister, my mom and her siblings look at each other and ask what to do. They each throw some dirt into the grave, a symbolic gesture. Yet there is laughter, too. Is there a wrong way to do a funeral? Afterward, we take pictures (some of them goofy). We go out to lunch at my grandma’s favorite restaurant. We share stories.

In my creative writing classes, I try to tell some of my grandma’s story, and the story of her parents. I am saddened that I no longer have grandparents to ask questions of, particularly at this time when I am most interested in learning more about my ancestors. While this is not my first time writing about grief, it is the first time I write about grief that is my own. My grief is mild. I was not particularly close with any of my grandparents, but we visited a few times per year. My mom’s mom lived a long life. But I regret not spending more time with her when I had the chance.

16 | Fear

In 2016, Allison and I welcome our firstborn son, Emerson. My perspective on life changes in an instant. I want to be there for him constantly. I want everything good for him. And I begin to have a new fear.

Before he was born, if you asked me “What is your biggest fear?” I would have answered, “Being trapped in a mudslide or a crevasse or underwater.” Now my answer changes: “My biggest fear is that any harm would come to my son, that my son would die.”

17 | Denial

On December 15, 2017, we move from an apartment to a rental house. We call it the “tap dance house” because when we toured it last month, Emerson loved to tap his shoes on the laminate floor.

On December 20, Emerson does not wake up from his nap. The paramedics arrive and take Emerson to Seattle Children’s Hospital. They cannot revive him.

Allison cries and throws herself on Emerson’s body, tucked into a blanket on the hospital bed. I am calm—a false calm. I am in shock. This can’t be real. This isn’t happening to me. I understand that this boy, my Emerson, is dead. But I can’t understand that he will not be coming home with me, laughing and pouting and snuggling like normal.

Finally, I begin to cry. I am out of practice. I get choked up at some moments in movies, but real tears, real sobs? I am out of shape. I have never mourned. I have never hurt like this.

18 | Grief

It is impossible to describe what I feel in this moment. I feel terror, like when the rock hit the bird. I feel longing like in all my dreams as a child. A loneliness like staring at clouds. I fear my own dissolution. I feel rage like only heavy metal and dubstep can fuel. I feel like I am falling into an abyss, writhing in pain like a lab rat filled with poison. I feel regret and guilt for everything I should have done differently that day. I shouldn’t have gone to work. I should have checked on him more often. I should have snuggled with him in the chair longer instead of putting him in his crib. I feel pain and pressure like I’ve been swallowed by a monster called grief.

I cycle through these emotions. I’ve felt them before. Only now they are intensified. They are made physical. My stomach hurts. My back hurts. My neck hurts. My throat hurts. My face hurts.

We take turns holding him in the bed. Family cycles through. Some friends arrive. We tell stories. We laugh. We sing to him. We pray. We cry.

Five hours later, around 9:00pm, we sing him his bedtime songs, pray, and leave him in the arms of our favorite nurse. She sings to him as we walk out the door of the room, as we walk out the doors of the ER.

We have a decision to make: where will we sleep tonight? I want my own toothbrush and pajamas. We go home. Can we call it that anymore? We’ve lived there five days. Our son is no longer with us. What is home? What can possibly be home for us now?

19 | Bargaining

Allison’s parents drive us home. A family vanguard gets to the house first, removes anything belonging to Emerson: toys, clothes, dishes. It all goes into his bedroom, the room he died in. The door is closed. When we get home, the toys he played with that morning, the dishes he ate from that morning, are as absent as him.

All night, I wake up weeping. All I can pray is “Why, God? Why?” My only hope is that there are still four days for God to work a resurrection like the raising of Lazarus.

20 | Denial

The next day is the darkest day of the year. Allison’s parents drive us to a nearby waterfront park. I took Emerson here four days ago. I have a video of him swinging on the swings overlooking Puget Sound. We walk down to the rocky beach and sit on a log. It is cold. We shiver. We throw some rocks in the water, a symbolic gesture. Emerson loved to throw rocks into the water. We pray.

I call my parents. I did not call them last night. My mom answers the phone, “Mom,” I say, then start weeping. I cannot even talk about his death. It is as if every word I speak is coated with grief. No word is free from the intensity of emotion I feel.

21 | Compassion

At the memorial service, we ask people to donate a stuffed animal. We would give them to various organizations in town. During the service, when people come forward to put their animals on stage, I weep. It isn’t their generosity that gets me. It isn’t simply that I miss Emerson. It is the fact that I have not seen most of these people since Emerson died. Grief has made me an entirely new person. I cannot fathom reintroducing myself to them as a bereaved father. (Even to this day, it is difficult to know how to share this part of my life.)

In the service, when it is our turn to share, Allison and I speak with confidence. During the planning stage, multiple people told us we didn’t have to be on stage, we didn’t have to say anything. “No,” we said, “we have to. We are compelled to speak.” We don’t cry on stage. We speak with confidence. We even make people laugh.

At the reception afterward, I am smiling. Not even at our wedding was there such an array of people from every era of my life. We accidentally cause a receiving line to form. People wait to speak with us. Almost everyone has a grave face on. And I am smiling. “How are you? Good to see you. Thank you for coming.”

Death is a personal, lonely experience for each of us. We face our own mortality alone. At the same time, death brings us together. Because we will all die, we are united in this common human experience. Experiencing the death of a loved one can awaken all sorts of emotions in us. Anger is still one of my deepest, most frightening emotions that has emerged through my grief. But grief can also arouse compassion for others. We all have or will suffer loss. We each carry unseen bereavements, traumas, sadnesses. Why not let that bring us together?