I’ve decided not to simply write a summary of my life to date, highlighting certain threads and events. Instead, I’m taking it slow. From time to time, I will write other “About Me” posts, each with its own flavor. Instead of a continuous story, I will share some snapshots, what Patricia Hampl suggests we call “vignettes,” the “unsorted heap of images we keep going through …, the makings of a life, not of a narrative” (The Art of the Wasted Day 100).

After all, our lives are not tidy, organized stories. Our lives are a series of juxtaposed situations. Story is the meaning we make from them.

But most of the moments of life are forgotten. What I do remember is like a chain of islands I must bridge with what I call “the story of my life.” It is a reconstruction, an artificial continuity. I don’t remember my life as it actually happened. I remember the story I tell myself about my life. And I continue to write and rewrite that story.

Another reason to write “about me” in occasional vignettes: I would rather write according to the way I think (which is like a web where everything connects) than according to the order things happened. Verlyn Klinkenborg argues that “writing is often an appeal not to the order of our chronological lives, but to the order of our internal lives, which is nonchronological and, in fact, unorderly” (Several Short Sentences About Writing 120–121).

So these “About Me” posts may seem randomly chosen, and perhaps that will be the case. But I believe much can be discovered by exploring the details and implications of these vignettes.

Okay, enough preamble. Here is the vignette for today:

When I was in third grade, I would repeatedly check out one particular book from the local library: The Dinosaur Dictionary. It was large and thick and had a shiny dust jacket. Inside were page-long profiles of over 600 dinosaurs,. I loved dinosaurs, and I loved being able to learn about new ones, ones my friends had never heard of, like Kentrosaurus and Micropachycephalosaurus and Parasaurolophus and Deinonychus and Compsognathus and Iguanodon.

The more time I spent with The Dinosaur Dictionary, the more I discovered a different love: words. I was fascinated by the Greek and Latin roots that made up dinosaur names. “Dinosaur” itself means “terrible lizard” in Greek. Micropachycephalosaurus means “small thick-headed lizard,” which I think would make for a superb insult. My favorite dinosaur is Deinonychus, which means “terrible claw.” It has one huge talon on its otherwise standard therapod foot. While all my friends were obsessed with the popular Velociraptor, I stuck to the similar, slightly larger—and in my opinion, superior—raptor, Deinonychus.

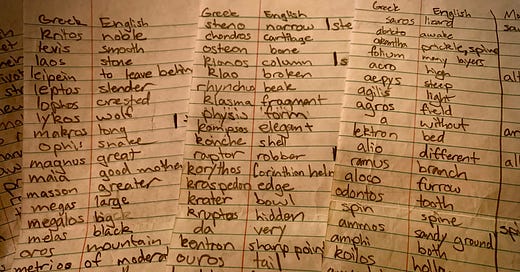

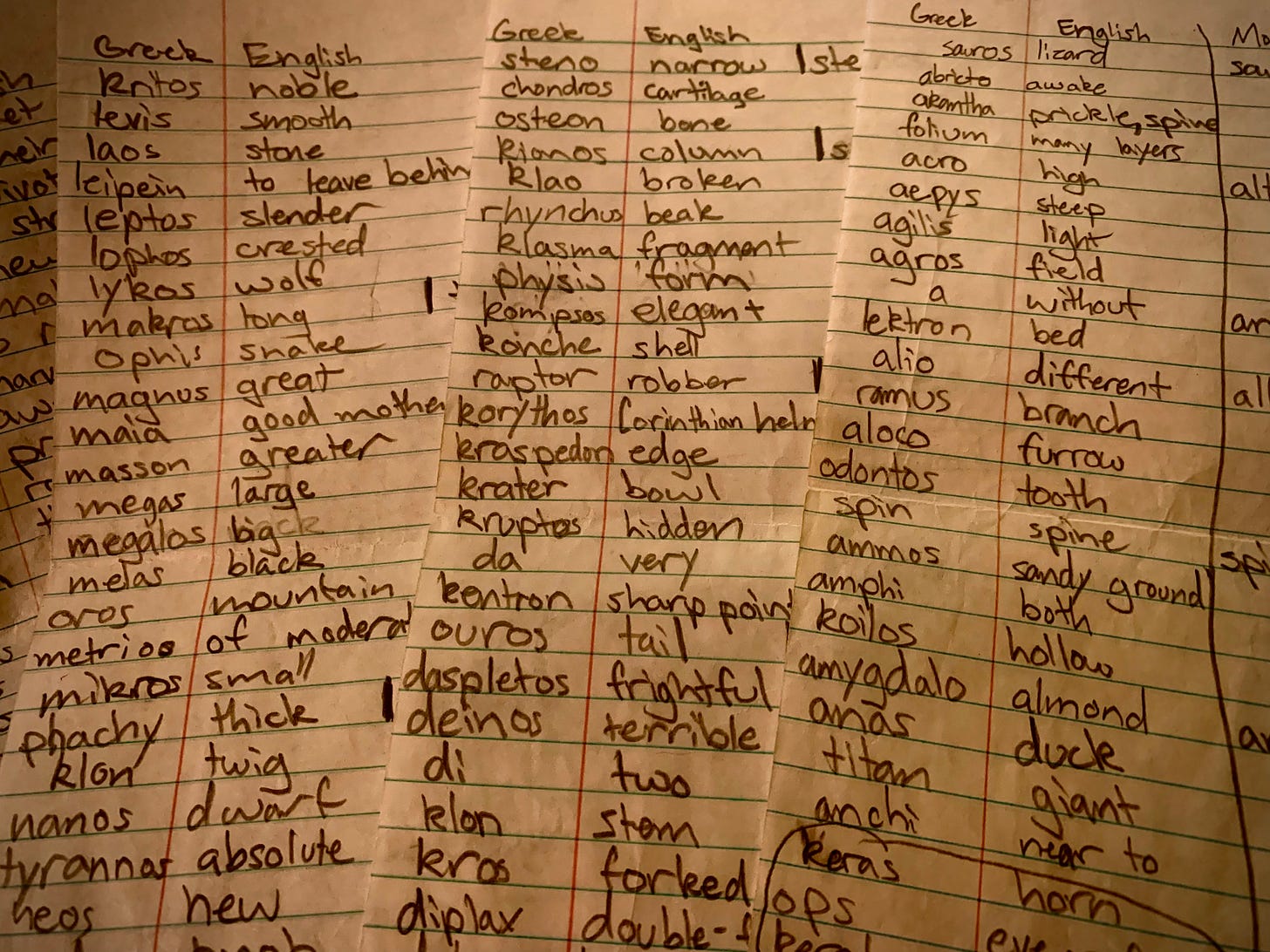

But it was the names rather than the details that fascinated me. I eventually began a list. I wrote as many Greek roots as I could find and their English equivalents. (For some reason, I did not like the Latin roots as much, avoiding them in my list, though some did sneak in.) In total I had four pages worth of Greek roots, front and back. I know it is four pages because I still have the list, one of the few remaining documents from my childhood. I took a picture for the banner image of this post.

In his book, Let Your Life Speak, Parker Palmer reflects on his childhood obsession with airplanes. Not only did he create model airplanes, but he put together books on aviation. He thought he would grow up to be an aerospace engineer or airline pilot. In time, he learned that it was not about the airplanes. It was about making books, about being an author. Palmer argues that even in childhood, our life is “speaking” to us about who we are.

With this in mind, what can I learn from my own vignette? What does my obsession with dinosaur names have to tell me? Why was I so keen on that aspect and not others? Here are a couple possible reasons:

Since childhood, I’ve loved making lists. Perhaps Greek roots of dinosaur names just happened to be convenient subject matter.

In adulthood, I learned that I have a knack for learning languages. When I took Koine Greek in grad school, I showed my professor the list I’d made twenty years earlier. Did the list-making foreshadow my interest in foreign languages?

A third reason seems most apt to me, however. I was learning about language (in a broad sense) and how to do things with it. After I had a quorum of Greek roots at the ready, I started to create my own dinosaurs. Around that time, I was also learning to draw dinosaurs. I would create the name of a new dinosaur then try to draw it. (On rare occasions I went the other direction: picture before name.) Sadly, I only remember one dinosaur I created: Altocervixosaurus, “high-necked lizard.” It was a tall sauropod which I decided should have a pair of spikes coming from the middle of its long neck. (When I showed my new creation to my mother, she told me I shouldn’t put “cervix” in the name of a dinosaur, no matter what it means. Of course, that went over my head at the time.)

This was one of my first explorations of language. I learned the definitions (or in this case, translations) of words, then I learned what they could do together, what effect different combinations made. Unconsciously, this is a model I’ve followed my whole life. In middle school, I started reading the dictionary. I got through A, C, I, K, N, P, Q, S, V, W, X, Y, Z. The songs I wrote at the time reflect my “exploration” phase. I would juxtapose solecism and paroxysm, teratogen and klatch, vituperation and annelid. Why? Because I could, because it was likely I was the first person to ever make such combinations of words. The songs were terrible, but the experimentation was valuable.

For me, that’s what writing is about. Exploration, discovery, experimentation. Play. I still make lists today, lists that are mostly useless games I play with words. Yet there is something in that experimentation that sharpens my understanding of language, of its possibilities. When I write, I enter a wide field of play.

Okay, so now you learned something about me (I learned something about me, too!). All that from one little vignette from childhood. Consider your own childhood. What is a vignette that you’ve remembered all these years later? What do you think that experience, that memory, can teach you about yourself?

Suggestions for further reading:

Patricia Hampl, The Art of the Wasted Day

Verlyn Klinkenborg, Several Short Sentences About Writing

Parker J. Palmer, Let Your Life Speak